An Interview with Marije Baalman

What is your background?

I grew up on the countryside in the Netherlands. When I was 18, I was leaving secondary school and needed to figure out what’s next. In that moment going to a music academy was not something for me, I had piano lessons for six years, but I stopped because I didn’t like playing sheet music. I also had a very dusty impression of conservatories. My music teacher was very old fashioned, so I didn’t really know about electronic or experimental music. But I continued improvising on the piano and creating my own music and made recordings of that. I was also writing a lot of short stories. I first seriously looked at the topic of linguistics, to do more with the writing. I went to an open day at the faculty in Utrecht. But I just didn’t feel at home in this sort of environment and needed to go in a different direction. I wrote to universities, where could I learn about sound in physics. This was before the internet, universities had no websites, so I had to figure out what makes physics in one city different from another city. One of the universities wrote back and eventually I ended up at the TU Delft, as they had a very strong acoustics department. I graduated in applied physics on a topic of room and perceptual acoustics. I took then a one-year course in electronic music at the institute of Sonology in The Hague, that allowed me to learn more about electronic music history, making electronic music and building my own instruments with sensors. My supervisor at the TU Delft was a guest professor in the electronic music studio at TU Berlin. Seeing a chance to combine acoustics and electronic music, I went there and was very lucky to get a last-minute grant to do postgraduate research, which turned into a PhD in the end. Meanwhile, I performed a lot in the Berlin noise scene. Somewhere along the line I got introduced to Chris Salter, with whom I first collaborated on an interactive dance project, and who then offered me a postdoc in Montréal at Concordia University. There I shifted into working with wireless sensing technologies in different performative contexts and responsive environments. After three years in Montréal I moved back to the Netherlands. I wanted to get out of academia because staying would have meant to teach. And what would I teach to students in an art school if I don’t know what is to be an artist outside of academics. I found that I needed some real-world experience, outside of the protected academic bubble. But I also wanted to be closer to my family. In Amsterdam I got hired by STEIM for 5 years as a hardware engineer, researcher and developer. Afterwards I became a member of the artist association instrument inventors initiative, that is where I’m now.

What are your experiences being a woman in the music technology field?

That’s a good question. In physics of 100 students that started there were only six women in the first year. But what was also interesting is that five of these women completed all the first year courses within the first year, which was a much higher percentage compared to the male students. Probably this points a little bit to the fact that a lot of women are discouraged if there are on the medium level at being good in technical subjects, while men are told ‘yeah you can do this’ etc. I had the privilege that I was able to learn very easily. In high school, I was at the top of my class and I got good grades in the university. That made it easier as people knew I was good at things. I was the first female developer contributing to the SuperCollider source code, that was back in 2014. Also, in the first few Linux audio conferences I was possibly the only woman present and at least the only woman presenting work. Nonetheless, I found both communities quite welcoming. During my time at STEIM there were a lot of international artists and musicians coming in and occasionally I got that remark ‘oh we never encountered a woman as a technical support’. Generally, people were okay with it. Sometimes I started to wonder, for example at a presentation of my work in Strasbourg where I did a solo concert and afterwards someone asked ‘Did you make all these things yourself?’ Later I was wondering if they would have posed this question the same way to a man. I also got invited to a lot of different programs focusing on women in electronic music, that has also been a platform where I presented my work.

Did you have a role model or mentor?

I had no specific role model. I just pursued what I found interesting. I had the privilege that I am good at learning things, and I could go in any direction (languages, physics, math). I also was quite persistent in what I wanted and what I was interested in. This combination probably helped me to get support and get noticed. My teachers were always very supportive. My mentor in acoustics, Diemer de Vries, introduced me to Folkmar Hein, the leader of the electro-acoustic Studio at the TU Berlin. Joel Ryan, one of my teachers at Sonology, introduced me to Chris Salter. These connections were important to get where I wanted to be. But I’ve also invested in going to conferences of topics that interested me, presented my own work there, and engaged in those kinds of connections. This helped me to build a good network.

Would you like to introduce more closely what you are currently working on?

The big project I’m working on now is writing a book called ‘Just a question of mapping - The ins and outs of composing with real time data’. This book is about how to create digital musical instruments and interactive environments, I’m looking at the whole scope of choosing and selecting sensors and controllers to connect these to output media. I’m trying to make a link between the aesthetic and the engineering considerations. With my hybrid background as both an artist and an engineer, what I see a lot is that engineers don’t always understand the aesthetics while artists don’t always understand the engineering possibilities. Sometimes I found that people come up with solutions where I think, yeah that could have been simpler or better thought through. Or artistic approaches with a naive concept of how a technology works and then don’t really get everything out of it or are aware of the limitations and biases that are in the technology. Engineers on the other hand - this is specifically in the NIME community sometimes a problem - can have quite old-fashioned ideas of what a musical instrument is or what musical practice is. They work from an old-fashioned model where you have a composer, you have a musician and then you have an instrument maker. I think in the current artistic practice this is not so clear cut anymore, but just one way of approaching music, especially when you look across genres. If you look at how different theories and practices of approaching compositions have developed, you will see that that has become much more reflective on the musical practice itself, and the socio dynamics in that; it is much more than putting notes on a paper or writing a score for performances. I’m trying to address this bridge between the artistic thinking and practice and the engineering.

What are your research methods?

It is really a mix. I did quite a few case studies for this, I studied specific works from several different artists all with slightly different projects and instruments. I have looked at a lot of different tool kits that are there for doing mapping, read a lot of papers and other books and then there are a lot of my own experiences. I tried to set up a method how to analyse these instruments and how to document them which has been difficult since there is a lack of vocabulary of how to talk about these things and how to document things outside the software they are developed in for example. If people write something in Max, they don’t know how to communicate what they are doing to someone who uses SuperCollider and doesn’t know what the different objects in Max do. As new programming languages are being developed, how can you transfer the knowledge that has been built up inside of these environments into new environments without reinventing the wheel? That is one of the concerns that I try to address, how to transfer knowledge from artist to artist and from project to project. Since the hardware is getting much more accessible, everyone is just starting with it but doesn’t know what to do. I hope the book will give some guidance in that, and become a handbook or reference.

What is the follow up?

I think it is kind of natural when you start writing a book that you know what the next book should be about. There are some more advanced topics that I wanted to cover in the book but that is just getting too much and would require too much work to do this so I decided there would be a next book which will give the opportunity to use a bit more of my own work as examples and red line in the book. I can go more in depth and use it to focus and analyse what I’ve been doing in past projects and future projects which are still happening. The topics there will be more about creating computational behaviours, systems that evolve based on real time interactions and explorations in machine learning and gesture recognition. At the same time this will help me to focus the artistic works that I still have in development and to reflect on past work.

What advice would you give to women who are interested in pursuing a career in music technology?

The short thing: Don’t give up. Pursue what interest you, try to learn what is needed. What helped me a lot is building up a network. Go to conferences and present your work, just don’t be shy about it. Engage in these conversations. When I look back, I think my parents were very encouraging. One example, we had this electronic learning kit from Philips at home when I was young and I was building these different things from it. Only decades later I heard that it was originally given to my brother, but I had more fun with that kit. Probably, my dad was enjoying it because he was also really interested in electronics. They just let me pursue what I found interesting. So don’t let anyone stop you. That is the main advice I can give.

Thanks a lot!

References

-

Marije Baalmans website https://marijebaalman.eu

-

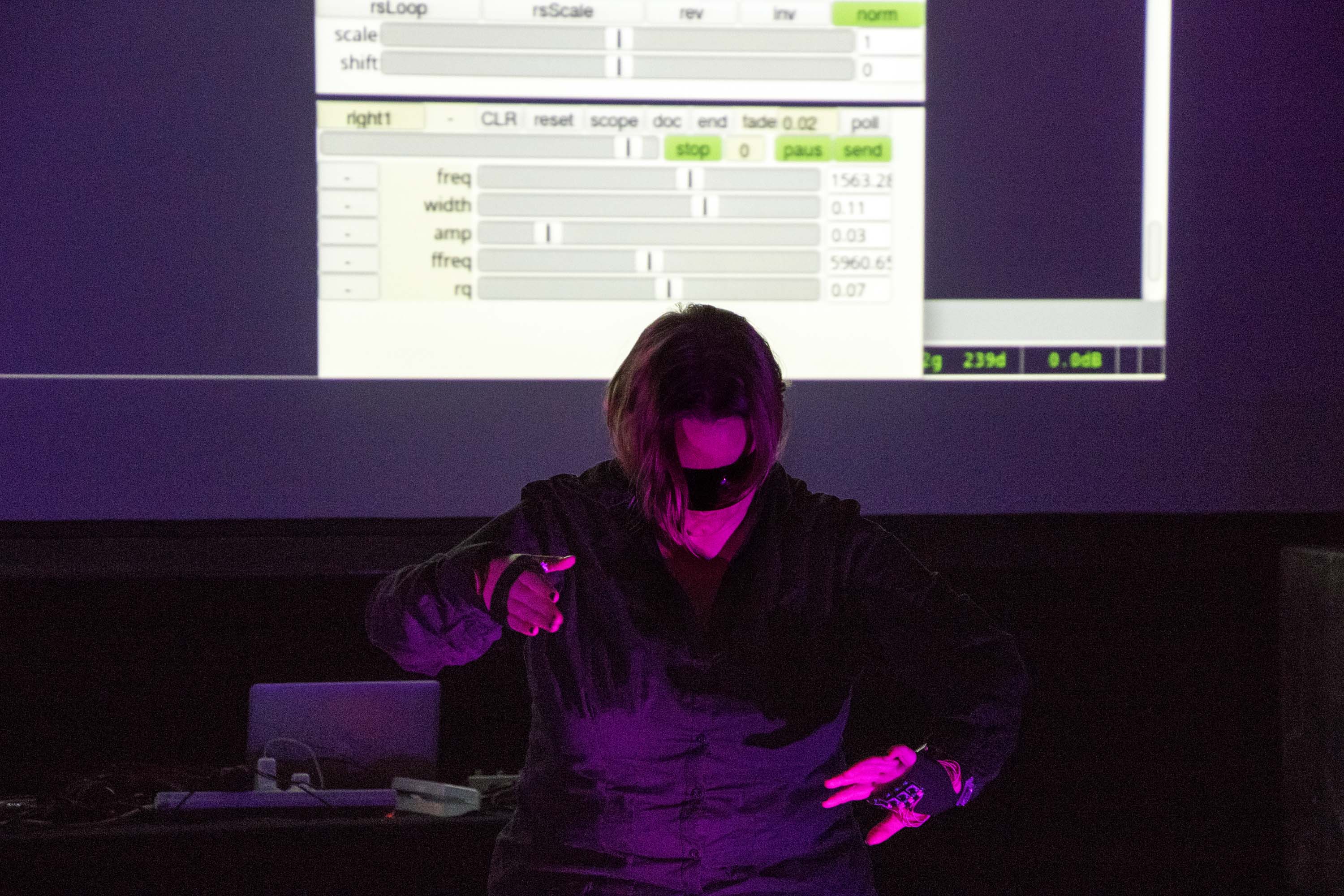

Virtual performance Wezen - Handeling at Engineered Expression, May 07, 2021

-

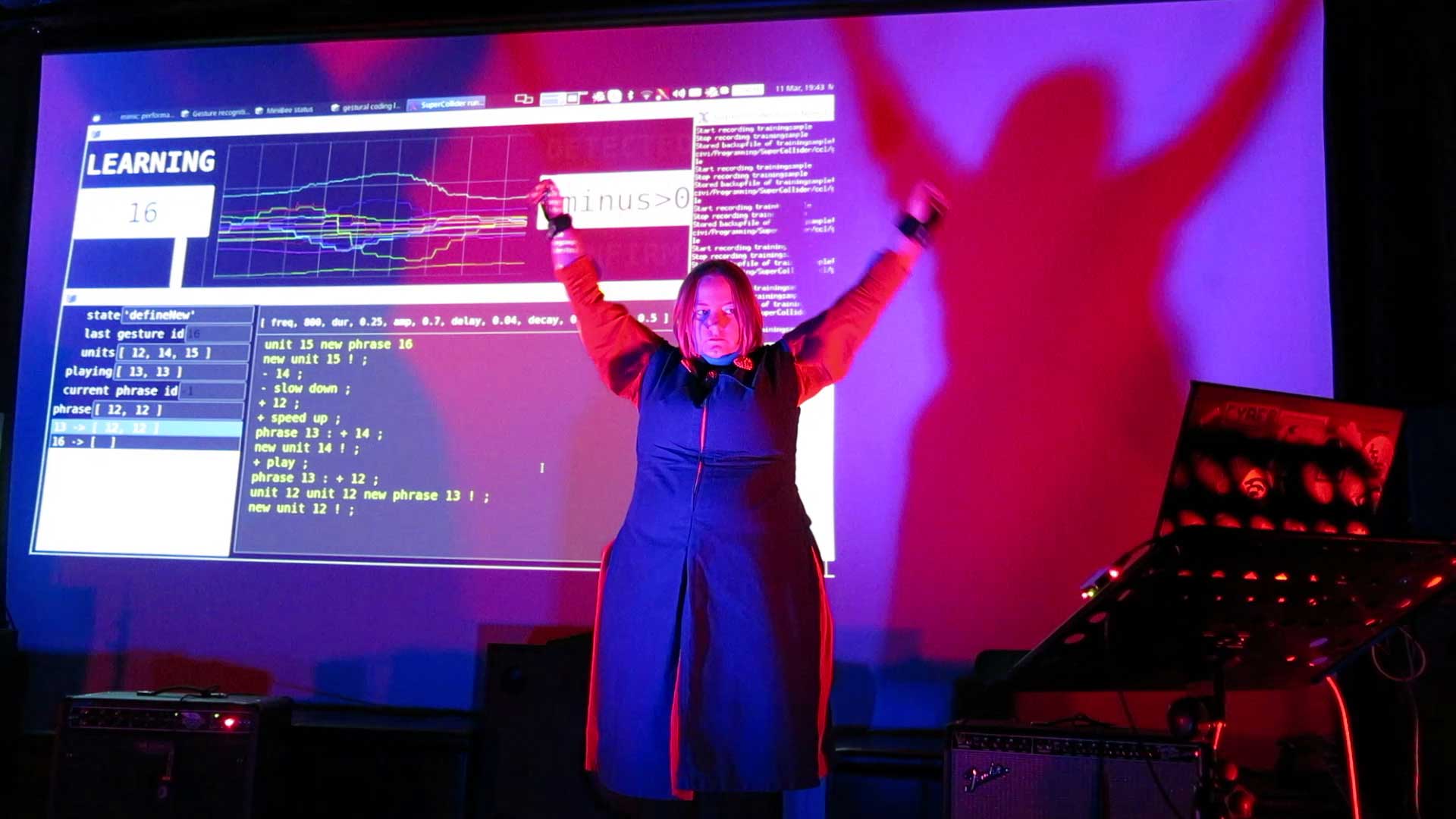

Live performance ‘The Machine is Learning’ at Live Interfaces ICLI, Trondheim, March 11, 2020

-

Mapping the question of mapping Marije A.J. Baalman | Colloquial paper | 2020 Live Interfaces, ICLI 2020, Trondheim https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/908792/908793

-

Embodiment of Code Marije A.J. Baalman | Conference paper | 2015 First International Conference on Live Coding, Leeds, UK, July 13-15, 2015 https://iclc.toplap.org/2015/html/72.html

-

Spatial Composition Techniques and Sound Spatialisation Technologies Marije A.J. Baalman | Article in journal | 2010

-

Organised Sound (2010), 15: 209-218 Cambridge University Press

-

Behind the Screens: Marije Baalman - An interview with livecoder and performer Marije Baalman.